The Whiskey Maker's Tale

How Quantum Satis rolled into the Whiskey crafting world

FAQHISTORY

5/8/20246 min read

"There are more stories in a glass of whiskey than in The British Library—provided you have the patience to read them."

The Philosophy of Quantum satis

How a Woman's Discerning Palate Led to Liquid Gold

There exists, dear reader, a certain species of gentleman who views the systematic consumption of spirits with the same enthusiasm one might reserve for systematic root canals. The founder of Quantum satis belonged precisely to this tribe of abstemious souls. Yet — and here begins our tale — he was not so rigid in his philosophy as to deny the occasional celebratory dram, particularly when shared in convivial company and savored with all five God-given senses at full attention.

Now, every great enterprise (or war) begins with a woman, and this story proves no exception to that eternal rule.

The founder's wife possessed what might charitably be called "refined sensibilities" when it came to potables. Vodka? Too brutal. Brandy and cognac? Positively barbaric. Even those sweet liqueurs that other ladies sipped with affected delight proved too aggressive for her delicate constitution. As for wine — well, wine was a lottery. Some bottles sang arias of terroir and sunshine; others tasted as though an angry grape had died in the bottle and held a grudge about it.

Beer, however — ah, beer! Here was a beverage of infinite variety, a rainbow of colors, a symphony of aromas, a palette of flavors that delighted rather than assaulted the senses. Beer became her festive companion of choice.

But here's where mathematics and matrimony collided most inconveniently. A small gathering of friends might politely dispatch one bottle of spirits, perhaps two of wine. Beer, however, required an altogether more ambitious arithmetic. And this was at the dawn of the new millennium, when recycling had become that peculiar modern penance — sorting glass from plastic, wondering whether bottle caps belonged with metal or miscellaneous, hauling the clinking evidence of merriment to collection points. Not to mention the Sisyphean task of hauling those heavy bottles from shop to home in the first place.

The founder, being a man of both logic and devotion (and subscribing firmly to the ancient wisdom that happy wife equals happy life), arrived at an elegant solution: he would craft his own beer.

A thought had struck him with the force of revelation: If the Natufians — those ancient people dwelling in caves thirteen thousand years ago — had mastered the intentional control of beer fermentation in the Rakefet cave, armed with nothing but stone tools and keen observation, then surely a man living in the third millennium, with all the accumulated knowledge of civilization at his fingertips, could manage the same feat? It seemed almost an insult to human progress to think otherwise.

Thus emboldened by thirteen millennia of precedent, what began as domestic diplomacy blossomed into artisanal triumph. The effort proved minimal; the results exceeded even optimistic expectations. His wife was delighted, their friends were impressed, and the carry-recycling crisis resolved itself beautifully — those bottles, like faithful servants, simply refilled themselves at home and returned to service. A perfect circular economy, achieved decades before it became fashionable.

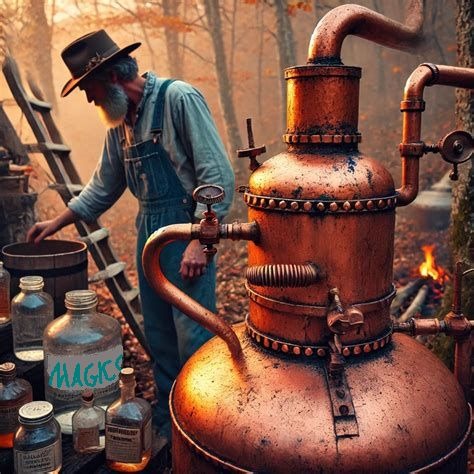

The Education of a Distiller

Yet our founder could not ignore a stubborn fact: many people — inexplicably, perhaps, but undeniably — preferred stronger spirits. What's more, the various traditions of tequila, cognac, grappa, vodka, schnapps, whiskey, and bourbon presented a fascinating puzzle. Each had its devotees, its rituals, its secrets.

So began his studies.

What he discovered would reshape his understanding entirely. Nearly every spirit, he found, lived within narrow organoleptic walls. Consider cognac: it must breathe vanilla and grape, perhaps with a whisper of other fruits hovering at the edges. The differences between one house and another? Merely a matter of intensity and texture. Some shouted their presence; others whispered. Some scratched at the throat like an angry cat; others descended smooth as silk. But the essential character remained remarkably constant. Voilà, as the French might say — you've met one cognac, you've met them all, more or less. And similarly, the other spirits are.

Then he encountered whiskey.

Here was a different beast entirely—a creature of infinite variety and personality. Whiskey, he discovered with mounting excitement, was the democratic spirit. Every expression found its constituency. Some souls craved darkness in both color and character; others sought sunshine in a glass. Some wanted their drink to fight back, to scratch and burn with honest aggression; others preferred it to slip down gentle as a lullaby. Some chased the ancient peat-smoke smell of Scottish bogs; others hunted tropical banana notes as though searching for paradise in liquid form.

The parallels to his beloved beer world suddenly crystallized. Beer's magnificent diversity came from its variables: the grain (barley, wheat, rye, oats, or cunning combinations thereof), the malting methods (dried, toasted, smoked — each technique a different door to a different room), the dozens of yeast strains (each adding its signature — dry, floral, fruity), the hops (offering a library of bitterness and flavor), and even the water (that most overlooked and essential element). Layer upon this the brewer's precision and cleanliness, and you had the recipe for both variety and consistency.

A worldwide community of natural intelligence — before we began calling it "artificial" — had mapped this territory completely. Methods documented, recipes shared, traditions preserved. You'd have to work impressively hard to miss something in the beer-maker's art; the knowledge stood freely available to anyone with curiosity and dedication.

The Challenge of the Spirit

But whiskey? Ah, whiskey presented an entirely different challenge.

Notice, if you will, that even the spelling divides into camps: "whiskey" versus "whisky" — a small distinction that carries considerable weight in certain circles.

The recipe seemed simpler on its face: no hops cluttering up the equation. The process began identically to beer-making, proceeding through fermentation of the wash. But then — then came the transformation. Distillation, filtration, aging, bottling — an entirely new art, a separate science, a different philosophy altogether.

And here's where tradition became both blessing and curse.

The whisky world cloaked itself in "tradition" — that most revered and most frustrating of concepts. Each country maintained its own orthodoxy: Scotland, Ireland, America, and the rest of the world, each marching to different drummers. Within Scotland alone, regional traditions diverged so dramatically you'd think you were sampling different planets. And each distillery? Each guarded its secrets like a dragon hoards gold.

Oh, they'd advertise the romantic details readily enough: the number of times the spirit passed through copper stills, the type of wood for aging (ex-bourbon, ex-sherry, virgin oak), the duration of maturation, whether the final product was blended or kept single. These were the selling points, the marketing poetry.

But the genuine secrets — the tiny nuances of still pot construction, the temperatures and the precise cuts during distillation, the optimal tooling, the water source chemistry, the appropriate measurements, the exact temperature curves of the aging warehouses — these remained locked away, passed from master distiller to apprentice in whispers, guarded more carefully than family jewels.

Therein lay the challenge that captivated our founder: to study these traditions, to excavate their strengths and expose their weaknesses, to experiment with each variable in the production chain, to understand how every single tool and substance influenced the final, noble liquid. This was detective work, scientific inquiry, and artistic expression rolled into one intoxicating (if you'll pardon the pun) pursuit.

The Proof in the Bottle

Quantum satis committed itself to this quest — to perfect the craft of whiskey-making through study, experimentation, and relentless refinement. That this wasn't merely hubris or hobby is evidenced by validation from the most objective of judges: international competitions, where Gold and Double Gold medals now rest in the Quantum satis trophy case, silent but eloquent testimony to achievement.

The Long Pour

So, dear reader, here's the story distilled to its essence:

The whiskey world is rich beyond measure — in history, tradition, and science. It ranks among the most popular yet still genuinely appreciated of recreational spirits, a beverage that facilitates both contemplation and conversation, solitude and socialization.

Natural curiosity — that most human of impulses — drove the Quantum satis founder to explore and systematize this vast, complex world. The practical proof of this research manifests in a carefully curated range of Quantum satis whiskies, each crafted not merely with care, but with the pursuit of perfection.

What began with a wife who preferred beer has culminated in spirits that would make that same lady (and indeed, anyone with a discerning palate) proud.

And isn't that, after all, the finest tradition of all?

Contact

Questions or thoughts? Reach out anytime.

info@quantumsatis.site

Phone: TBD

© 2026. All rights reserved.